With kids back in school now, Seasonal Wisdom reflects back on an inspiring World War I program that made millions of children “soldiers of the soil” in the United States School Garden Army – and growing your own food educational and patriotic.

Nearly 100 years later, Seasonal Wisdom sits down with University of California academic Rose Hayden-Smith to discuss these early school gardens and her acclaimed new book Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Surprisingly, these historic programs are more relevant than ever today.

A Little History

Before this story gets started, however, I need to make a confession.

This well-known historian and I have a history together.

To the world, Hayden-Smith is a highly sought-after speaker, author and academic with the University of California. Her knowledge about wartime gardens, food systems and sustainable agriculture is renowned. She’s a former W.K. Kellogg Foundation Food and Society Policy Fellow. The White House Project named her one of the nation’s thirty most influential women in sustainable food systems. In 2013, she was honored with UC Davis’ Bradford-Rominger award for her distinguished work in agricultural sustainability. In other words, she really knows her stuff.

To the world, Hayden-Smith is a highly sought-after speaker, author and academic with the University of California. Her knowledge about wartime gardens, food systems and sustainable agriculture is renowned. She’s a former W.K. Kellogg Foundation Food and Society Policy Fellow. The White House Project named her one of the nation’s thirty most influential women in sustainable food systems. In 2013, she was honored with UC Davis’ Bradford-Rominger award for her distinguished work in agricultural sustainability. In other words, she really knows her stuff.

But to me, this talented, hardworking professional is simply “Rose” – a charming and cheerful lady, who I’ve known for more than a decade. She has actually been my neighbor TWICE; most recently, when my family bought a house nearly across the street from her a few months ago. But that’s another story.

You may recall Seasonal Wisdom’s earlier interview with this captivating historian about Victory Gardens a few years back. You can see Rose talk about Victory Gardens with Joe Lamp’l on PBS-TV’s Growing a Greener World.

In her new book Sowing the Seeds of Victory (McFarland; 2014), Rose examines the various national gardening programs of World War I.

In her new book Sowing the Seeds of Victory (McFarland; 2014), Rose examines the various national gardening programs of World War I.

What many people don’t realize is that the Victory Gardens of World War II actually had their origins in the lesser-known Liberty and Victory Gardens of World War I (1917-1919). And Rose makes a compelling case that these progressive wartime programs continue to provide lessons nearly a century later.

U.S. School Garden Army

Sowing the Seeds of Victory covers in detail federal gardening programs, such as the National War Garden Commission and Woman’s Land Army. But as a fan of getting more kids in the garden, I was particularly interested in the United States School Garden Army.

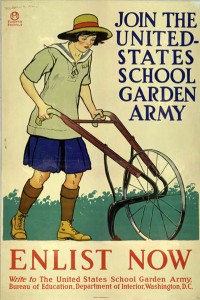

Launched during World War I, the United States School Garden Army was a federally promoted educational program with the slogan A Garden for Every Child. Every Child in a Garden. Developed by the Federal Bureau of Education, the national gardening curriculum for urban and suburban youth was funded by the U.S. War Department (now the Department of Defense). Yes, you read that correctly.

Launched during World War I, the United States School Garden Army was a federally promoted educational program with the slogan A Garden for Every Child. Every Child in a Garden. Developed by the Federal Bureau of Education, the national gardening curriculum for urban and suburban youth was funded by the U.S. War Department (now the Department of Defense). Yes, you read that correctly.

“President Woodrow Wilson himself made the decision to fund an army of school gardeners, affirming that their work in gardens was of great importance to national security,” writes Rose in Sowing the Seeds of Victory. “Wilson used money from the National Security and Defense Fund.”

This historic program represented an unprecedented governmental effort to make agricultural education a formal (and informal) part of the public school curriculum.

With so many kids growing up on junk food, and not knowing how to garden today, it cheers my heart to think of an army of students learning about cultivating and preserving homegrown vegetables and fruits, courtesy of U.S. government defense dollars.

Our conversation about the United States School Garden Army:

SW: How did you learn about this army of student gardeners? Is it very well-known?

Rose: I learned about it by chance in an obscure reference in an article by O.L. Davis, probably in the fall of 2002. I was immediately hooked. Why had no one heard about this or written anything but a short article?

SW: What did you find the most fascinating about this national group of student gardeners?

Rose: Several things. The United States School Garden Army was likely the first federal curriculum from the nation’s Bureau of Education, and it elevated gardening and food production – and education about that – to an act of vital importance to national security, an act of civic virtue, of patriotism … all within the context of wartime.

SW: How did this school garden program reflect what was happening in our nation’s history at that time?

SW: How did this school garden program reflect what was happening in our nation’s history at that time?

Rose: The U.S. School Garden Army reflected progressive impulses, notions of experiential education, “sheltered” childhood, and it used imagery and rhetoric, such as propaganda and World War I poster art, to influence youth and engage them. The historic garden program also reflected federal concerns about food security, rural depopulation and the declining number of U.S. farmers. These school gardens sought to reconnect rural and urban American, and to build unity around the war effort.

SW: So, what type of impact did this program have on society?

Rose: Through this and Liberty/Victory Garden programs, as well as food preservation/conservation programs (under Hoover’s food administration), the U.S. was able to greatly increase food exports to our European allies and feed the nearly 3 million newly drafted American troops.

It also reinforced – in my opinion—a sort of ethos around the culture of gardening/farming that has remained a consistent strand in American thought. It was an important act of civic engagement.

SW: Wow, it sounds like this little-known wartime school program had quite an impact.

SW: Wow, it sounds like this little-known wartime school program had quite an impact.

Rose: Yes, the U.S. School Garden Army impressed upon youth participants how to cultivate food, and how vital that was to national security and personal health.

The program empowered youth to take action at school, at home and in their communities. This was a collective action that united youth, and it provided a vital means of educating youth about the important of agriculture.

SW: So, what are some of the ways this World War I program is still relevant nearly a century later?

Rose: Lots of reasons. The number of American farmers continues to decline. Youth still need to know where their food comes from. All Americans should acquire basic food cultivation skills.

There is nothing more important that we could be teaching youth than how to grow food, why farming is important, about human nutrition, food waste, food conservation, sustainability and environment. It all ties to improved academic performance and science achievement if done properly – and also with improved nutrition and health. And the civic aspect is unbelievable. There is an opportunity with the new Common Core curriculum to once again embrace this sort of integrated approach to education. We should seize it!

SW: Thanks for your time. Is there anything you’d like to add?

Rose: “A garden for everyone. Everyone in a garden.”

SW: That’s good advice even today.

Why do you think children should be taught to garden and grow food today?

Connect with Rose! Her blog, her book

More Stuff: Learn more about Victory Gardens. See how Victory Gardens inspire community gardens, such as Chicago’s Peterson Garden Project

{ 1 comment }

Very interesting article! I will definitely buy these books! They should be read!

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 2 trackbacks }